Why Nursing Costs Are Reshaping Retirement Plans — A Systematic Look at Market Shifts

You’ve saved for retirement, but have you truly accounted for nursing costs? As healthcare demands rise, so do long-term care expenses — quietly eroding retirement security. I’ve watched friends scramble, caught off guard by bills they never saw coming. This isn’t just about aging — it’s about how market trends, from insurance shifts to real estate for senior living, are redefining what it means to retire well. Let’s unpack this systematically, without hype, just clear insights on protecting your future.

The Hidden Threat Lurking in Retirement Plans

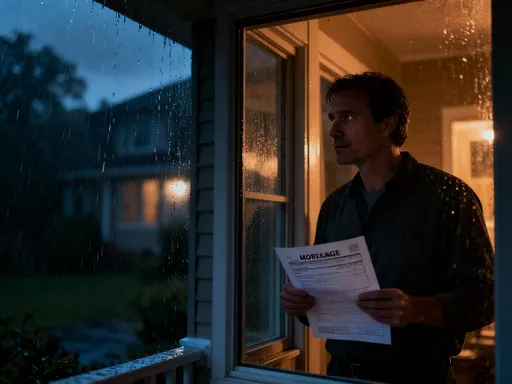

For decades, retirement planning has centered on predictable threats: inflation, stock market volatility, and outliving one’s savings. Yet, one of the most significant financial risks — the need for long-term nursing care — remains underappreciated and often unaddressed. Unlike a market correction, which may recover over time, the cost of nursing care can persist for years, draining assets at a steady, relentless pace. Consider the typical scenario: a retired couple in their early 70s with a well-funded 401(k), a paid-off home, and a modest pension. They’ve budgeted for travel, dining, and occasional home repairs, but not for a potential five-year stay in an assisted living facility. When one spouse develops chronic health issues requiring daily assistance, the family is forced to confront a reality few retirement calculators account for — the average annual cost of a private room in a nursing home now exceeds $100,000 in many U.S. states. This single expense can deplete a lifetime of savings in less than a decade.

The failure to anticipate long-term care costs stems partly from psychological bias. People tend to plan for what they can easily envision — retirement parties, grandchildren’s graduations, or a dream vacation — but not for declining health or dependency. Financial models often reinforce this blind spot by focusing on income replacement rates and portfolio longevity without factoring in the probability of needing skilled nursing. According to data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, about 70% of people turning 65 today will require some form of long-term care during their lives. Despite this, fewer than 10% of Americans have long-term care insurance, and even fewer have set aside dedicated funds for care. The gap between expectation and reality creates a dangerous illusion of security. Many retirees assume Medicare will cover nursing home stays, but in truth, it only pays for short-term skilled nursing following a hospitalization, not custodial care. When the bill arrives, families are often left with no choice but to liquidate investments, downsize homes, or rely on family members to provide unpaid care — decisions made under stress, not strategy.

Another contributing factor is the variability in care needs. Some individuals may never require more than occasional home help, while others face years of intensive support due to conditions like dementia or mobility loss. This uncertainty makes planning difficult, but not impossible. The key is recognizing that long-term care is not a fringe risk — it is a central component of financial well-being in later life. Retirees who ignore it are effectively gambling that they will be among the lucky few who remain fully independent until the end. A more prudent approach treats nursing costs as a probable expense, not a remote possibility, and integrates it into the core of retirement planning. By doing so, individuals can avoid last-minute financial triage and preserve both their savings and their dignity.

How Market Trends Are Fueling Higher Nursing Costs

The rising cost of nursing care is not an isolated phenomenon — it is the result of deep structural shifts in the healthcare and housing markets. At the heart of the issue is demographic change. The U.S. population is aging rapidly, with the number of adults over 65 expected to surpass 80 million by 2040. This surge in demand for senior services has not been matched by a proportional increase in supply, particularly in skilled caregiving. There is a growing shortage of certified nursing assistants, home health aides, and licensed practical nurses — roles that are physically demanding, often underpaid, and subject to high turnover. As providers compete for a limited workforce, wages have risen steadily. While this is a positive development for workers, it translates directly into higher operating costs for care facilities, which are passed on to consumers.

At the same time, regulatory requirements for senior care facilities have become more stringent. States now impose stricter safety standards, staffing ratios, and training mandates to ensure quality and reduce liability. These measures, while necessary, add layers of expense. For example, a facility that once operated with one aide per ten residents may now be required to maintain a one-to-six ratio, effectively increasing labor costs by 40% or more. Compliance with fire codes, accessibility laws, and infection control protocols also requires capital investment in infrastructure upgrades. These fixed costs must be absorbed through higher resident fees, contributing to the upward pressure on pricing.

Real estate plays an equally important role. The cost of land and construction in desirable areas — particularly suburbs with access to medical centers and transportation — has soared in recent years. Developers face higher interest rates, material costs, and zoning restrictions when building new assisted living communities or memory care units. As a result, new facilities often target the high-end market, pricing out middle-income seniors. Even existing properties face rising property taxes and insurance premiums, further squeezing margins. The combination of high demand and constrained supply has created a seller’s market, where providers can raise rates with little competitive pressure to hold them down.

Investment trends have also reshaped the landscape. Over the past decade, private equity firms and real estate investment trusts have poured billions into senior housing, viewing it as a stable, long-term asset class. While this influx of capital has led to modern, amenity-rich communities, it has also introduced profit-driven management practices. Investors expect returns, which means facilities must maximize occupancy and revenue. This can lead to aggressive pricing strategies, reduced staffing flexibility, and a focus on healthier, more independent residents who require less care — effectively pushing higher-need individuals toward more expensive medicalized settings. The result is a fragmented system where cost and access are increasingly determined by market forces rather than medical need.

The Insurance Paradox: Protection That’s Hard to Access

Long-term care insurance was once hailed as the solution to the nursing cost dilemma. In theory, paying premiums for years in exchange for coverage during a future care event makes sound financial sense. Yet, in practice, the market has struggled to deliver on that promise. Today, fewer than 3% of Americans aged 50 and older hold a traditional long-term care policy, down from nearly 2% in the early 2000s. The decline is not due to lack of need, but to a series of missteps by insurers and changing risk calculations. In the 1990s and early 2000s, many companies underpriced policies, assuming that claim rates would remain low and investment returns would offset payouts. When people lived longer than expected and interest rates fell, insurers faced mounting losses. In response, they raised premiums dramatically — some policies saw increases of 50% or more — making coverage unaffordable for many policyholders.

At the same time, underwriting standards have tightened. Insurers now scrutinize applicants’ medical histories with greater care, often disqualifying those with conditions like diabetes, obesity, or a family history of dementia. This creates a cruel irony: the people most likely to need care are the least likely to qualify for insurance. Even those who are healthy may find premiums prohibitively expensive. For a 60-year-old couple in good health, a policy with $200 per day in benefits and a three-year payout period can cost over $4,000 annually — a sum that may rival their property tax or car payment. Over time, the cost of maintaining coverage can outweigh the perceived benefit, leading many to let policies lapse.

In response, the industry has introduced hybrid products that combine life insurance or annuities with long-term care benefits. These policies allow policyholders to access a portion of the death benefit to pay for care, or to receive a monthly allowance if they qualify for assistance. The appeal lies in the guarantee: even if care is never needed, the policy still provides value through a death benefit or return of premium. However, these products come with trade-offs. They typically require a large upfront payment — often $50,000 or more — which may not be feasible for middle-income households. Additionally, the care benefits are often limited in duration or amount, and accessing them may reduce the payout to beneficiaries. While hybrids offer more flexibility than traditional policies, they are not a universal solution.

The result is a market where protection exists in theory but remains out of reach for most. Consumers are left navigating a complex landscape of incomplete coverage, high costs, and uncertain eligibility. For many, the decision to forgo insurance is not a choice, but a necessity. This underscores the need for alternative strategies — not just insurance, but a broader financial framework that prepares for care costs through savings, asset management, and risk mitigation.

Investment Strategies That Align With Rising Care Needs

Given the limitations of insurance, retirees must look beyond traditional coverage and consider how their investment portfolios can help offset future nursing expenses. The goal is not to speculate for high returns, but to build a resilient financial foundation that can withstand the shock of long-term care costs. This requires a shift in mindset — from viewing retirement savings as a source of income alone to seeing it as a buffer against major health-related expenditures. A well-structured portfolio can provide liquidity, steady income, and growth potential, all of which are essential when facing unpredictable care needs.

One effective approach is to allocate a portion of assets to dividend-paying stocks, particularly those in the healthcare and consumer staples sectors. Companies that produce medical devices, pharmaceuticals, or essential goods tend to generate consistent revenue, even during economic downturns. Their dividends can provide a reliable cash flow that supplements Social Security or pension income. While stocks carry market risk, a diversified selection of high-quality, low-volatility dividend payers can offer both income and long-term appreciation. Reinvesting dividends during the early years of retirement can help compound growth, while selectively withdrawing them later can help cover care-related costs without selling principal.

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) focused on healthcare facilities represent another strategic option. These trusts own and operate senior housing, medical offices, and rehabilitation centers, earning income from rent and occupancy. As demand for senior care grows, these properties tend to maintain high occupancy rates, providing stable returns. Healthcare REITs are also less correlated with the broader stock market, offering diversification benefits. While they are subject to interest rate fluctuations and regulatory changes, their long-term leases and essential nature make them a resilient asset class. Including a modest allocation — say 5% to 10% of a portfolio — can enhance income while aligning with the demographic trends driving nursing costs.

Bond portfolios also play a critical role in risk mitigation. High-quality municipal and corporate bonds provide predictable interest payments and preserve capital. In a rising care cost environment, bonds can serve as a safety net — assets that can be liquidated with minimal loss when needed. Laddering bond maturities ensures that funds become available at regular intervals, reducing the need to sell during market downturns. Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) add another layer of protection by adjusting principal with inflation, helping to maintain purchasing power over time. Together, these fixed-income investments create a foundation of stability that supports more aggressive growth assets.

Risk Control: Building Buffers Without Overexposing

Protecting retirement savings from the impact of nursing costs is not just about what you invest in, but how you manage withdrawals and allocate resources. The challenge lies in balancing immediate needs with long-term sustainability. A sudden health event can force retirees to tap into their nest egg at an inopportune time — such as during a market downturn — leading to irreversible losses. Therefore, effective risk control involves creating financial buffers that allow for flexibility without compromising future security.

One proven strategy is to establish a dedicated health reserve — a portion of savings set aside specifically for potential care expenses. This reserve can be held in liquid, low-risk accounts such as high-yield savings, money market funds, or short-term CDs. Having this fund in place reduces the pressure to sell investments at a loss when a care need arises. The size of the reserve should reflect individual risk factors, such as family health history and current wellness. For many, a reserve of $50,000 to $100,000 provides a meaningful cushion without over-allocating to low-growth assets.

Another key technique is the use of layered withdrawal strategies. Instead of drawing from retirement accounts in a linear fashion, retirees can structure withdrawals to prioritize tax efficiency and market conditions. For example, in years when the market is down, it may be wise to withdraw from cash reserves rather than selling equities at a loss. In up years, retirees can replenish the reserve, creating a dynamic balance between growth and protection. This approach, often called a “bucket strategy,” segments assets into time horizons — short-term for living expenses, mid-term for health needs, and long-term for growth — allowing for disciplined yet adaptable spending.

Estate planning tools can also enhance risk control. Trusts, for instance, can help manage assets for long-term care while preserving eligibility for certain public benefits, though they require careful setup and professional guidance. Additionally, coordinating with family members about potential caregiving roles and financial responsibilities can prevent last-minute crises. Open conversations about expectations, resources, and preferences reduce emotional strain and ensure that decisions are made thoughtfully, not reactively.

Practical Moves Anyone Can Make Today

Not everyone has the luxury of decades to prepare for rising nursing costs, but meaningful steps can be taken at any stage of life. The earlier one begins, the more options are available, but even those nearing retirement can improve their financial resilience with deliberate action. The key is to move from passive worry to active planning, using tools and strategies that are accessible and realistic.

One of the most impactful moves is evaluating home equity. For many retirees, their home is their largest asset. Options such as downsizing to a smaller, more manageable property can free up significant capital. The proceeds can be used to fund a health reserve, pay off debt, or invest in income-generating assets. Alternatively, a reverse mortgage can provide a steady stream of tax-free income without requiring monthly payments. While reverse mortgages come with fees and interest, they can be a viable option for those who plan to stay in their home and need supplemental cash flow. The decision should be made with full understanding of the terms and long-term implications, ideally with guidance from a financial counselor.

Another practical step is reviewing employer-sponsored benefits. Some companies offer retiree health benefits, long-term care insurance subsidies, or wellness programs that can reduce future medical costs. Even if coverage is limited, understanding what’s available can inform planning decisions. Additionally, Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) remain one of the most powerful tools for tax-advantaged savings. Funds in an HSA can be used tax-free for qualified medical expenses, including some home care services. Unused balances grow tax-deferred and can be withdrawn for non-medical purposes after age 65, making HSAs a flexible resource for future care needs.

Finally, seeking professional advice is one of the most valuable investments a retiree can make. A fee-only financial planner with experience in retirement and long-term care planning can help assess risks, evaluate options, and create a personalized strategy. The cost of advice is often outweighed by the value of avoiding costly mistakes. Free resources, such as those offered by nonprofit aging organizations or state health departments, can also provide reliable information on local care options, benefit programs, and planning tools.

Rethinking Retirement Security in a New Era

Retirement security is no longer defined solely by how much you’ve saved or how long your portfolio can last. In today’s environment, true financial well-being includes the ability to manage one of life’s most uncertain and costly phases — long-term care. The rising cost of nursing is not a distant threat; it is a present reality reshaping how families plan, invest, and protect their futures. Ignoring it risks turning a hard-earned retirement into a financial crisis. But by acknowledging the challenge and taking systematic, informed steps, individuals can build resilience and maintain control.

The path forward requires integration. It means combining market awareness with disciplined investing, proactive risk control, and realistic planning. It involves viewing long-term care not as an afterthought, but as a core pillar of financial health — as essential as housing, food, or transportation. This shift in perspective allows retirees to move from fear to preparedness, from reaction to strategy. It empowers them to make choices based on clarity, not panic.

Ultimately, the goal is not just to survive retirement, but to live it with dignity, comfort, and peace of mind. By addressing nursing costs head-on, families can protect their savings, reduce stress, and ensure that the later years are defined by fulfillment, not financial strain. The tools and knowledge exist. What’s needed now is the willingness to act — thoughtfully, deliberately, and without delay.